ERNEST FRUEHAUF

[Andy Miles] Hello, and welcome to “Resistance, Resilience and Hope: Holocaust Survivor Stories,” a podcast co-production of Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center and Studio C Chicago.

The mission of Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center is expressed in its founding principle: Remember the Past, Transform the Future. The museum is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Holocaust by honoring the memories of those who were lost and by teaching universal lessons that combat hatred, prejudice, and indifference. The museum fulfills its mission through the exhibition, preservation, and interpretation of its collections and through education programs and initiatives, like this podcast, that foster the promotion of human rights and the elimination of genocide.

On this episode, we hear from Ernest Fruehauf.

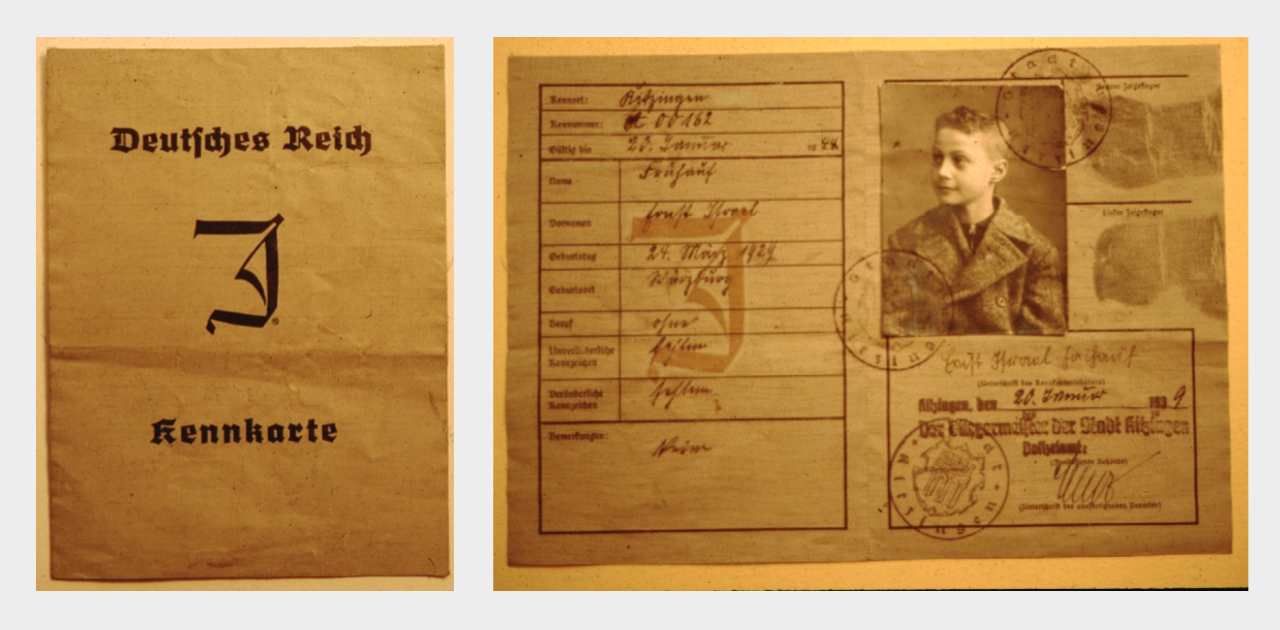

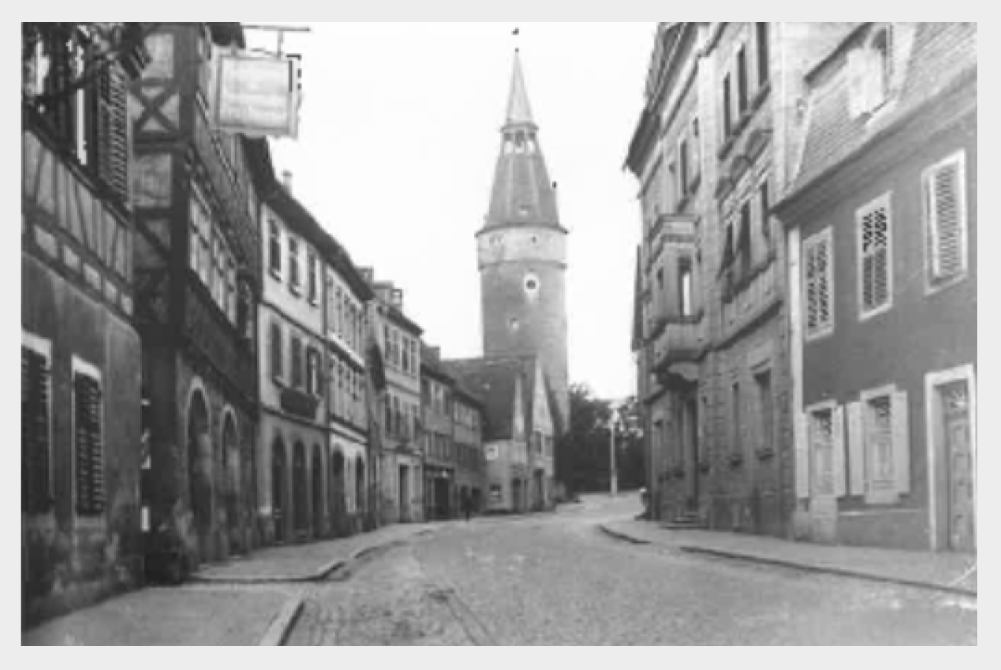

Ernest was born in 1929 in Kitzingen, Germany, where his family owned a successful café located below their second-floor apartment. As a young child, Ernest experienced the rising tide of hate and antisemitism in Germany. On November 10th, 1938, during the events of Kristallnacht, an angry mob ransacked the café. His father was arrested and imprisoned at Dachau concentration camp, and his family was forced from their home to live in a community building, or Juden Haus. Ernest's father knew his family was in danger. Following thousands of Jews, he arranged to flee Germany in 1941. Although arranging refuge in the United States was difficult, his father remained undaunted and, sponsored by a relative here, the Fruehaufs got out of Germany just in time.

[Ernest Fruehauf] "We were lucky. Exactly in May of 1941, two weeks before Roosevelt closed the consulates in Germany altogether, we got our visas in the city of Stuttgart. We were lucky. And I thought, if it had been two weeks later, we wouldn't have gotten a visa anymore."

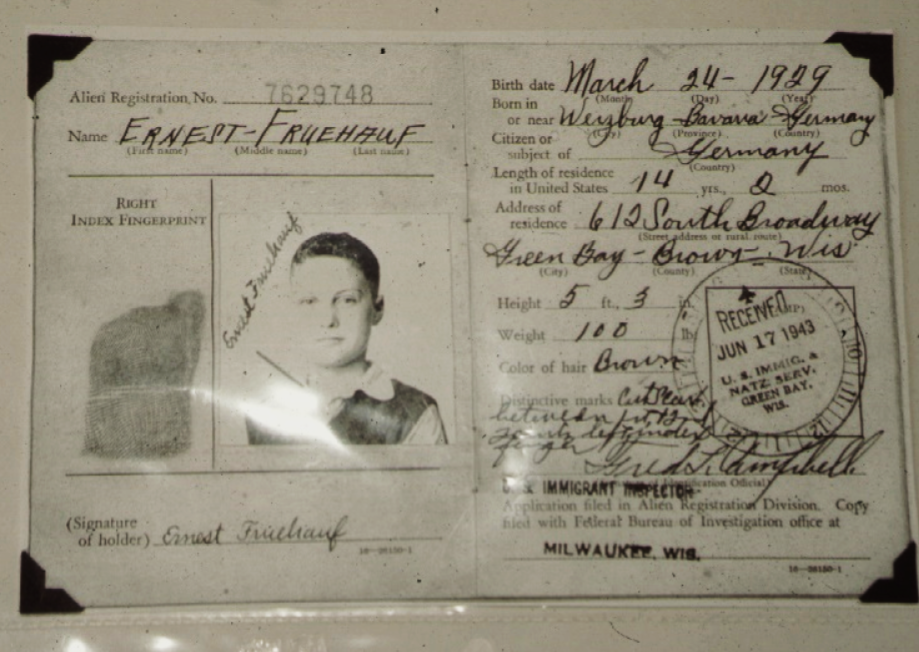

[Andy Miles] In 1941, 12-year-old Ernest Fruehauf arrived with his family in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where his mother's sister and family lived. After graduating from high school, he attended the University of Wisconsin School of Engineering and got a job with the Amoco Oil Corporation, now BP, retiring in 1989. He and his wife of 67 years, Ursula, live in Deerfield, Illinois, and have three daughters, five grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

We spoke over Zoom.

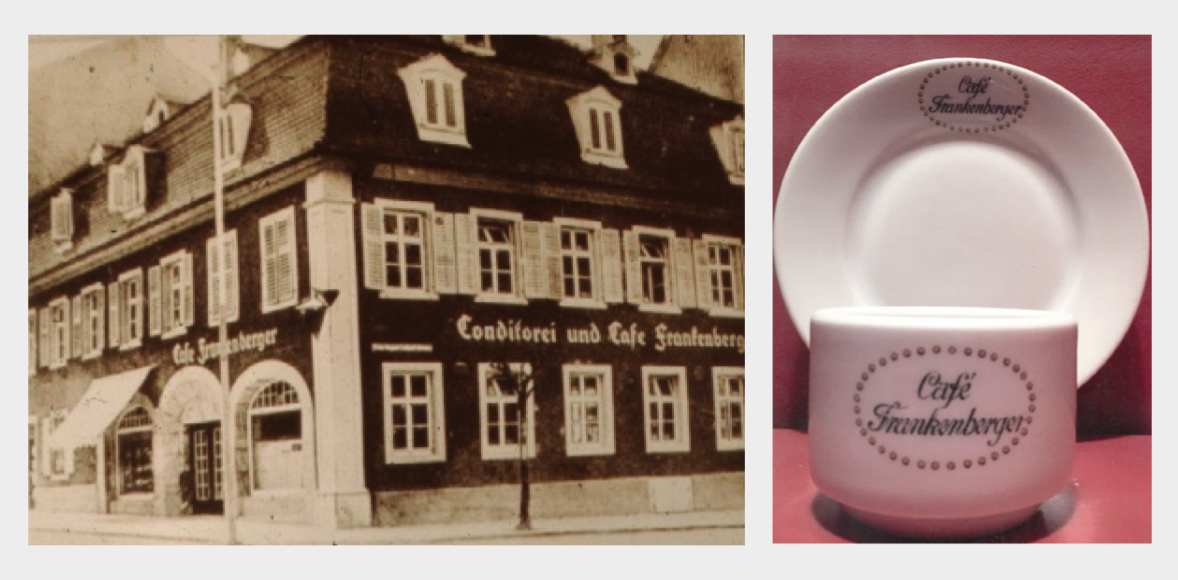

EF: My grandfather, to start with, started out a confectionery shop, and then my grandfather bought a larger place somewhere around 1912, I think. And he opened up a café, which was like a large Starbucks. So people could come in, sit down at tables, order all kinds of delicacies. My father and grandfather were superb confectionery bakers. And you could order all kinds of things. They also had chocolates. You could sit down and play cards. You could play chess. You could read newspapers. You could sit there, just drink coffee. We had waitresses who waited on people. And of course, I got to know a lot of the people as a youngster, and people knew who I was because I was my parents' first child.

After a while, certain people would come in all the time, you know, and they'd say, “Oh, Ernest, is your father feeding you too much cake?” and things like that. And so I got to know quite a few of the people. And I had a good time, and of course, I knew some of the children. But most of the time, because my folks were busy, I was pretty much kept around the café.

AM: And from the photo I saw, it was quite a big place.

EF: Oh, yes. Yes. It was well known. Our customers were both Jewish people but, of course, non-Jewish people as well.

AM: What would you tell me about your parents? I know your father was quite a large man and your mother was quite a small woman. (Laughs.)

EF: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, my father was six foot — maybe six foot one, but he was also very strong. He left home at age 13 because he wanted to become a baker. And he started working first as an apprentice and as a journeyman to learn the bakery business, particularly the bread and rolls business. Later on, he got a job in Silesia for a small Jewish bakery there. And when the owner was drafted into the First World War, the woman, although she had sons, she picked my father to be the one to manage and run the bakery, which he did. And so he started very early.

He was very strong. He had to make bread mixes, dough, by hand, so his hands were huge and he was a very, very strong man.

And my mother — like you said, she was very short. She was, I don't know, I think less than — I'm sure less than five feet tall — four feet something. But they got along very well with each other. They loved each other. They supported each other. I don't recall any serious arguments between the two of them at all. My mother worshiped my father. And he obviously had a very endearing love for her as well.

Interesting enough, because they were so busy working, the individual who was closest to me was my grandfather. He was a very decent, honest, and also good businessman. He was a very righteous individual who was very careful to follow the rules of — particularly as it relates to people dealing with each other. He was really a wonderful human being.

He used to take walks, because as he got older and my father, you know, was used to the bakery shop and everything else, he did most of the work. My grandfather would take his cane; he would go walking around the town. And one day he came home and he was totally beside himself. It must've been, I would guess, around 1934 maybe, give or take a year. And he was totally beside himself. He had walked down the street and he saw a former customer coming toward him. Now, by that time already, the Nazi party had let it be known, because of their boycotts that they had of Jewish businesses and so on, that Christian people — or let’s say non-Jewish people; they didn’t necessarily have to be Christians — didn’t want to be seen going into a Jewish bakery shop. So this man was one time obviously a customer and my grandfather knew him. So he saw this man and he said, “Oh, good morning, Herr So-and-So.” As the man went by him, he spit in his face. That so shocked my grandfather, it just totally floored him. And after a while, my mother saw to it that he wasn't going to walk around anymore.

AM: So getting into the mid-’30s, you said that as late as 1936 you hadn't really noticed changes taking hold; you attribute some of that to Hitler toning down some of the antisemitism for the Berlin Olympics.

EF: Because of the Olympics. They took down signs and tried to keep quiet, for a while.

AM: Yeah. Before we get into when things did markedly change, could you talk about the sense of anti-Jewish sentiment that you might have seen around you?

EF: Yeah. There were a couple of things that I would say I noticed.

First of all, around 1935, I think it was, the German government, Nazi government passed the Nuremberg Laws. And any German woman who was younger than 45 years of age could not be hired by a Jewish enterprise. So we had to let our waitresses go. They were nice young ladies. So that was one thing that changed.

By that time, of course, the number of customers decreased, too, substantially. First of all, non-Jewish people would rarely now come into the bakery shop, not that they didn't want to, but they were afraid that people would say: “Hey, I saw you going into the Frankenberger Café. What's the matter with you? That’s a Jewish establishment. You don't go in there.” And of course, youngsters, too, would see this sort of thing. That made it even more dangerous because they would tell their buddies and the word would get around. So they literally stopped coming.

What else? I noticed that — I began to notice the frequent marches of the SA, the so-called Brown Shirts, and the SS, what they called the Sicherheits, security police who would march with their uniforms. And they also — they would sing songs and you'd hear anti-Jewish comments. They would sing that “We won't be happy until” something like “Jewish blood spills from our knives.”

AM: And were these songs that they were just kind of making up on the spot?

EF: The words were probably made up, I would guess. And the melodies — some of them might have been made up too. I don't know. I just remember some of the words. And I used to — I didn’t like noise either, so I was somewhat reluctant to be outside. I would run inside and hide because I didn't like the noise. They sang very, very loudly.

But Hitler did, in about 1935 or so — I don’t know, ’35, ’36 — he began to build a huge army base outside of Kitzingen. And at this army — well, to start off with, they built barracks and they brought in young men and they were dressed in what you might call labor uniforms, brown caps, brown uniforms, and they would march through town, every morning coming out of — going out of town in the afternoon, coming back and going back to their barracks. And of course, they would sing songs. They wouldn't march quietly. It's not the customary thing to do. But they had these shiny spates. They were as shiny at the end of the day as they were in the morning when they left.

But anyway, when I saw the SS men, I always saw them as huge, tall, blonde guys. They had to be at least six feet tall, had to be in their 20s, blue eyes, blonde hair. And they wore totally black uniforms from the boots coming up to their knees, to their trousers, the jacket. The hat was black and had cross bones on the top, I think. And invariably, they would lead a German shepherd dog, who was, again, invariably muscled. If I saw them coming toward me on a particular side of the street, I would cross over to the other side. I didn't want to be anywhere near that. Dogs scared the living daylights out of me in those days.

So I would say, certainly by 1937, there were things going on around me in the community that made it obvious that I'm not one of them, so to speak. So, for example, we would go to school in the morning. School started the same time as public schools did and ended the same time. And now, we found — I would find myself accosted by maybe three or four of the German youth and they would start trying to beat up on me. Well, I tried to defend myself as best as possible. There's always a limit. So the board of the school decided, the community decided better we start school 15 minutes later to give us time to get there on our own and not have to worry about non-Jewish students, and be let out 15 minutes early.

The other thing: You probably have heard that this whole Nazi system was based on a kind of a three-stage system of disposing of the Jews. One of them was you have to identify them. The second one was to separate them. And the third one was to get rid of them. You know, by that time you decided, “Well, they’re vermin; you don't want to be around them. And so the best thing to do with vermin is to kill the vermin.” So it's a three-stage system.

AM: So I want to get into 1937, but before I do that, I started thinking, when you were talking about your reaction to harassment, I just was curious to know, how would you describe yourself during these years? What kind of boy were you?

EF: Well, what kind of boy?

AM: You didn't like noise.

EF: It’s an interesting question. I didn't like noise. I also didn’t like to get into fights. I wasn't particularly afraid, strangely enough. I often thought about that. For instance, there would be a carnival coming into town every summer and I would go over there. And for a while, I was able to do that. I must've been maybe six, seven years old, possibly eight at the most. But pretty soon, it became obvious that I better not go be seen there because I could tell the kids would see me and they looked like they were ready to beat me up. And I began to sense there is a limit — (laughs) — of what I can, I cannot do.

I saw signs in store windows. I saw the newspapers, but in newspapers you could make out what was going on. And I would see the newspaper on the way to school and home from school. It was usually taped onto store windows, where they published the paper, and I could read it. And I could see there was always a page that was obviously dedicated to hatred of the Jews. And the title always was, “The Jews are our misfortune.” And I remember that from being a youngster.

So there were certain things that I just picked up on my own. I also have to say that there's a lot that was probably going on my folks simply didn't want me to know. They would say, Ernest, go to school, come home, have a good time, play with your friends, do whatever you can, and don't worry about those things. They don't have to bother you; just forget about it.

But it was obvious by about 1938 or so that the children began to know who we were and, of course, kids, you know how children are. So we would go walking along the — on Saturday afternoons we’d walk along the Main River. And very soon we had these young boys decked out in their Hitler Youth uniforms and a scabbard and all that kind of stuff, and they would see us coming and they'd say, “We're gonna kill you, dirty Jews; go home, you dirty” — you know, I remember that. And here are little kids already talking that way. You don’t realize what happens — you realize that they're being taught all this.

AM: And how old were they?

EF: Oh, I would say they were eight, nine maybe; not much older than I was. They teach those things early.

AM: And eventually, the café had to post a “Jewish establishment” sign.

EF: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. I don't remember that specifically, but I know my father told me there was a sign there that said, “This is not an Aryan establishment” or something. I wasn't old enough at the April 1933 or ’34 when they had the nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses.

Things really became alive after November ’38, the so-called Kristallnacht situation. That's when I began to realize that life was not going to be the same anymore.

My father thought for a while in ’37, because things got a little bit more lively again after the year of the Olympics, that maybe we ought to consider leaving the country. My father wrote to America, my grandfather’s sister, and said, you know, maybe you could make some arrangements where we can leave the country.

So anyway, things went along, day in, day out, without really much of a change, until of course this business with Kristallnacht came around.

We knew nothing. The night before, on November 9th already, where it started in some communities — I learned about this; my mother told me the next day. They had a few Jewish men who were sitting around in the café downstairs playing chess. And came midnight, the game hadn't finished yet and my mother got upset and says: “Hey, I want to go to sleep. You can come back tomorrow. This chess set is going to sit here just the way you left it. Nobody's going to touch it. You can finish it tomorrow.” And one of the single guys, who incidentally was in the German army in the First World War — he was in the German intelligence service, Jewish guy, very nice gentleman — he said to my mother, he says, “Erna, how do you know we'll be here tomorrow?” It was a very amazing kind of a comment.

And it turned out very early in the morning — it must've been, I don't remember — certainly after six o'clock, maybe seven o'clock — November; it was already still dark then. There was a tremendous amount of noise on the street. What is going on? And pretty soon, I heard the downstairs store being smashed in. Then I heard the crashing of utensils and the cracking of wood and the breaking of the dishes, you know. It made a tremendous amount of noise. That went on for quite awhile. And at some time later, maybe eight o'clock or so, either some police or SS or Gestapo, two or three people came storming up to the second floor and they came to arrest my father and grandfather to take them to the city jail. And my mother went over there about, I don't know, maybe 11 o'clock or so, and the officer in charge, whatever, said, “You can take your father home; he’s so old we don’t keep him here.” He was over 60. He was already beginning to get senile. He wasn’t himself anymore, the same way he had been. My father — “He stays here. We'll keep him here. We'll let you know.” Well, he was kept there. We didn't know what happened. We found out later that he was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. He was there from late November to December 22nd, I think it was, something like four weeks.

So, in the meantime, things all of a sudden quieted down. Well, we had lunch. We got worried. We helped drag some of the mattresses up to the attic because we were afraid — how did we know that people wouldn’t come back and come into the house and beat us up? There were some homes where people were beaten up. So we dragged all this stuff up to the attic so we could sleep there at night. We didn’t want to be caught downstairs. Not that easy.

So about two o'clock in the afternoon, thereabouts, there was a lot of noise on the street. Here were whole groups, a large group of younger people, maybe teens, 20s, I don't know, and they were carrying torches and they were also carrying sections, the leather sections of the parchment of the synagogue scrolls. They must've taken them out and they burned it, maybe dance around with it. Who knows? They were halfway burned already. And they were throwing them on the cobblestone streets and they were putting them on fire and they were dancing and singing songs. That went on for a little while. I managed to get up close in the window to see what was happening. And I saw these young people doing all this dancing around. And I said, I remember thinking to myself, well, these are the first books of the Bible, so part of the Christian Bible too. Don’t these people know what they're doing? (Laughs.) You know, one of the problems of hate, you don't know what you're doing. They were burning everything.

It was early in the morning. Now, we're up in the attic and we hear a boom, boom, boom downstairs. Oh my god, what's going on? Well, it turned out to be my father. He was at the door. His hair had been shaved off. He had a black and gray prison uniform on. He looked like hell, because, you know, he was a strong man, but even a strong man, after a few weeks, two, three weeks in a place like Dachau begins to show.

AM: You said he'd lost about 20 pounds.

EF: That's my guess. Oh, yeah. I don't remember the exact, but he was certainly skinnier. And with that uniform on, he looked scary, and his hair all cut off.

So we sat down. My mother had made some coffee and we talked about things. He did not tell us what happened there. They told him if we find out that you tell anybody what happened to you here, we're going to arrest all of you and you're never going to see the light of day again. My father didn't talk about it. They would have hours upon hours of just standing at attention, not moving. There were people who simply fell over. They were older people. They passed out. Some died. They had Nazis who were brutal, sadistic people, but they were told you cannot kill anybody, but you can beat them up. Go as far as you can, but don’t kill them; we don’t want you killing them.

AM: So when your father had returned, he sat down and said that we need to get out of Germany.

EF: We have to get out. So he immediately wrote a letter to Washington to my mother’s aunt, and she realized that the game was up. So we wrote them a letter and we said, you've got to get us out because you know from the news what's going on; we're not going to be alive if you don't get us out.

So her husband had a brother who had a dime store somewhere in New York state and they had friends, and among them they got together enough money to satisfy the State Department of the United States, where they would send us a letter and said, OK, you are now eligible to get a visa. This is now spring of ’39 already, by the time all this was settled. Then they said, but you understand there is a depression and jobs are hard to get and there are not many openings. There's a quota system. And the best we see is that you'll get a visa in May of 1941. So that would be two years away.

AM: Those two years, from ’39 to ’41, that's a pretty perilous couple of years.

EF: Yes. They sure were.

AM: And the war started in September of ’39 and air raids began and food rationing.

EF: Oh, yeah.

AM: What memories stick out from the two years you lived in Germany during the war?

EF: That’s a good point. Well, first of all —

AM: And what was your mindset during that time? I mean, were you —

EF: We were a little bit afraid. We didn't know what might happen, but I was only, what — in ’39 I was, what, 10 years old. I had a lot of confidence in my parents, and certainly my father and mother did not want to get us upset about anything. They kept everything very quiet.

My father was — since he had no job, he was put to work in a very interesting position.

The Nazi party in our town created a pig farm. They raised hogs for the market. Now, you have to feed these pigs. So what they did, they took — I think there were four Jewish young men — my father was one of them — and they were given a wagon. And these guys would push this wagon around town and collect organic garbage. And this garbage, they would then take at the end of the day to this farm outside of town, mix it with milk and God knows what else, and they would have to feed it in the trough here to all these hogs.

He came home one day and he was disturbed. Something didn’t go right. So what happened? It was in the wintertime and there was snow. And the people hadn't gotten around to shoveling snow yet in the street, particularly — certainly not the sidewalk. They built a sled for the wagon. They tied the sleds onto the wagon so they could push it through the snow. And as they're coming toward a hill — they're trying to push this thing up the hill — they said, “Oh, the sidewalk is clean here; we’ll go on the sidewalk.” But they weren't on the sidewalk very long when down the sidewalk comes a woman with a baby carriage. Said, “Oh, we can’t push her into the snow.” So they pushed and pulled in order to get the sled off into the street before she came by. Well, this woman was obviously a Nazi because she had the guts to call the police department afterwards — or Gestapo, better yet — and tell them she was accosted by a bunch of Jews who were pushing a garbage wagon up the hill when she was coming down, so the police called him in.

Well, the police in Kitzingen knew my father. My father had been used for a number of jobs in this entire period, when he wasn't in the bakery anymore, after he came back from Dachau. They would sent him to north Germany in harvest time to harvest sugar beets. So they couldn't really say anything bad about him.

Anyway, this woman came down; she called the Gestapo, so my father got called in. The others were called in, too, of course. So they went to the police department and the police officer said, “Look, I know all you people, but I know that you wouldn't possibly be so stupid as to make comments about the German woman or anything else; you would just do exactly as you said you did. I'm going to tell Gestapo that I had you come in and I gave you a very severe verbal thrashing. And I’m going to tell them that I told them in no uncertain terms that if you ever get caught again, we’re going to take you and put you back to concentration camp or kill you. You have no right insulting a fine German woman.” And he said, I think it'll go by. And it did. It went by. They could have had him shot.

It was probably — I often thought about it — probably a positive thing in the long run because the police in the town knew him well and they could let the American government now know that if they let us into the United States of America, they'd have a good citizen on their hands, because whenever they needed somebody, they would call my father.

So we were lucky. We were lucky. Exactly in May of 1941, two weeks before Roosevelt closed the consulates in Germany altogether, we got our visas in the city of Stuttgart. We were lucky.

AM: And can you tell me about the exit itself? I mean, how did it all come together?

EF: We had a brother-in-law, distant family, who got us tickets on a Portuguese ship in Lisbon, and it was slated to leave at a certain time in July. And we were able to get tickets through a German countrywide organization that got us tickets on a special train, which was arranged through the national Jewish organization with the German railroads to take us from Berlin through France — German-occupied France — Spain, and Portugal.

So anyway, we get to the Spanish border. There’s a German officer there and he must've been one of the nice German officers because I still remember him saying, as I was coming by, he says, “Good luck to all of you,” you know, which is unusual. There were decent people anyway. You know, they weren't all bitter Nazis.

When we got to the first town, the town was in rubble, but there was a restaurant there. My father was itching for some hot coffee. So we went inside, sat down, the five of us. My father brought along — because he made bread at home, so he had the heel of a rye bread left over, maybe something larger than my fist. And when the waiter brought the coffee out to us, he pointed to that bread to himself, could he have it? My father said sure, gave it to him.

We sat there. We could hardly drink the coffee. It was made from potato peels. It wasn't coffee at all. And he came back and he gave us what was basically a smaller size shopping bag, about yay high, and he said from him to us. We said, you know, danke schön, thank you, whatever we knew. And we said, what did he give us? It was unbelievable. To this day, we talk about it as one of the greatest exchanges ever made in life. He gave us oranges, bananas, a pineapple, I remember, and maybe some other fruit, which was like gold to us, you know. To me it was the greatest exchange that I ever made.

AM: So in 1941, you successfully made the passage to the U.S. I wanted to ask you: What impressions or expectations did you have coming to America? And then, you know, what did you find when you got here?

EF: Yeah, well, actually, I wasn't sure what people would be like because some of the comments I heard these people make, the Americans at the consulate. The Americans in the consulate, I’m sorry to say, they were Nazis, without question. The way they treated us was so horrendous. It was unbelievable.

But what I thought — I thought, well, when we get to America, we'll have a whole new life. We can walk around the street. We can go to carnivals. We can eat more food. We have relatives. I expected things to be real nice, you know.

AM: And at that time, the United States had not entered the war, because that was —

EF: No, no. Right.

AM: yeah — still a few months away.

EF: Still a few months away. Right.

And I thought, well, if it had been two weeks later, we wouldn't have gotten a visa anymore. And I think they stopped the ships in October already before Pearl Harbor. So we just made it.

AM: Well, I was going to say, even though the U.S. hadn't yet entered the war, those seas were still dangerous.

EF: Oh, yes, because there were submarines and everything else.

The British, in fact, stopped us one day and they boarded the ship and they were looking for things that might be of value in their war effort or maybe they're looking for spies, maybe they're looking for materiel. They forced us into Bermuda Harbor and we spent a couple of days there, I think, while they ran through everybody's suitcases, books and everything else to see if they could find anything.

So then we got to New York and they were going to discharge us on the East Harbor, the East Side of Manhattan Island. Well, we got off the ship. The first place, I mentioned earlier, we went to was New Haven, Connecticut. That was an interesting experience seeing America for the first time.

So my uncle said one day: “Ernest, what are you doing sitting around here reading? Why don't you go out and walk two blocks this way and then two blocks that way and you can go — there's a swing; there are things that you can do. You could go out and enjoy yourself.”

So I go out there and I sit on the swing and I'm going back and forth. This is August, of course; it's vacation time. And I'm swinging back and forth, and all of a sudden, I see three young boys coming toward me. I said, uh-oh, do they see me as a stranger? They're going to beat me up? What's going to happen? I got a little bit tense. I didn't know what to do. Well, what happened was I had been given a watch. My father had bought one for me in Germany already from my bar mitzvah. So this watch — probably light was shining off of it. They could see the light that this guy's got a watch. And they came over and they asked me, what time is it? Oh, time! Oh, of course, this is America. They're not going to beat me up. They said thank you and they walked away. So now I know I'm free. (Laughs.)

AM: And you had managed to get out of Germany just in time —

EF: Oh, absolutely.

AM: — because by 1942, everyone in the town was deported. All the Jews —

EF: In fact, all the children I went to school with — there was one other little boy that got away and his father. But on March 24th, 1942, they were all deported from the railroad station. So what was interesting about it is that’s my birthday, March 24th. Can you imagine on my birthday being deported to God knows where? They didn't know where. Yeah, most of them were gassed almost right away, one place or another.

My grandmother died, as I told you, at the end of 1942. She was gassed.

AM: So when you arrived here and then during the years of the war, do you remember ever telling people about what you had escaped from?

EF: Well, I think most of the people had some knowledge of it. You know, don't forget — to be honest, we didn't really know because it was kept quiet. We didn't really know what the Nazis were doing to the Jewish communities of Europe. There were people who came over here who told Roosevelt, who let top government officials know, they let newspapers know, but they said, you know, we can’t confirm this. How do we know this is really happening? And Roosevelt wanted to keep it quiet because he didn't want the world to think that we’re in this war to save the Jews; “we’re in this war to defeat Hitler.” And so word didn’t get out. He knew about it from 1942 on, because there were people from Poland and other places who came over here, knew what was happening, and it was all kept very quiet. So we didn't know. They said, well, you know, he's happy to be in America. It's very nice here. And of course I was. But no, it was a shocker to us because we had no idea.

AM: I mean, you still had the experience that you had and your father had been sent to a concentration camp. But you just didn’t know the extent of what was —

EF: Of course. We knew that things were not good. We knew that they were going to be in trouble. There wasn't going to be enough food. And no doubt there was going to be killing going on. But I don't think any of us had any idea that they were being taken in special transports to places particularly in Poland, away from Germany, where they were gassing them in factories. I don't think anybody — I say that because I know my father was as amazed as anybody else. He was shocked, of course. He never understood what was going on.

Interestingly enough, my brother's wife works at the Jewish museum in Battery Park in New York. She looked up all the numbers and she said between 1933, when Hitler came to power, and 1945, only in ’39 was the German and Austrian quota filled. And she said, based on the available quotas, the Americans could have offered visas to at least 200,000 people and saved them. But of course, there was a depression in this country. And let's face it, from what I've read in history, because of the shortage of work and everything else, and Roosevelt was a good politician, he didn't want to upset his status by allowing a couple hundred thousand German Jews to come in here. What they could have contributed to the American system, that’s beside the point. He was not going to let any more Jews come in here than necessary.

AM: One of the last questions I want to ask you, Ernest, is, you know, why do you tell this story?

EF: Because I think the world needs to understand and know that although we're all made in the image of God, somehow or other, some of us get perverted and get the wrong lessons and they can’t solve their problems and they find somebody who they can blame for it, what’s called a scapegoat, you know. It goes on to this day. And I tell the story because I hope that I can influence at least a few kids to think about what can happen and what kind of a world they are living in and what kind of a world they could be living in if they're not careful.

If I could just convince a couple of kids not to get involved in this hatred business, I’ll have accomplished something.

[Andy Miles] You've been listening to “Resistance, Resilience and Hope: Holocaust Survivor Stories,” a podcast co-production of Illinois Holocaust Museum and Chicago’s Studio C. If you'd like to learn more about this episode and the series in general, please visit ilholocaustmuseum.org or studiocchicago.com/holocaust. And please share this podcast, rate it, and subscribe.

I'm Andy Miles and I'd like to thank executive producers Marcy Larson and Amanda Friedeman for their assistance and guidance in bringing this podcast to fruition, Ernest Fruehauf his time and candor, and I'd like to thank you for listening.