Toronto: City in Transition, an audio documentary (2003)

“It’s been a rough year for Canada’s largest, wealthiest and most powerful city. If Toronto was a business rather than a city, its stock would be selling for pennies today. Analysts would be trying to determine whether it had reached bottom. The answer probably would be not yet. Maybe not even close to it.”

“Toronto: City in Transition” is an audio documentary that examines numerous public policy issues in an effort to (1) portray the city’s visible decline during the past 10 to 15 years, (2) determine the causes of that decline, (3) survey proposed remedies to combat that decline.

From there, the documentary chronicles the changing racial/ethnic complexion of the city and Toronto’s rapidly growing population, exploring the ways in which these issues relate – whether in fact or only senseless reaction – to the decline.

Andy Miles (then working under the name Stephen Miles) traveled to Toronto in early September 2002, staying in the Beaches neighborhood over a 10-day period. He interviewed numerous scholars, journalists, a best-selling author, municipal politicians, city planners, and the proverbial man and woman on the street. Returning home in mid-September, he recorded several more interviews by telephone from the production studios of WLUW-Chicago and WORT-Madison.

Research was begun in August 2002 and completed in early January 2003. Scripting occurred between November and January. Miles produced the documentary as an independent academic project for the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Journalism & Mass Communication. In April 2003, he received a 2002-03 Academic Excellence Award for the project.

Contents

Banner by Yael Gen. All photos by Andy Miles.

Impressions

The City That Worked

The Homeless

Free Trade

Mega-city

Poverty

Housing

30-Year Plan

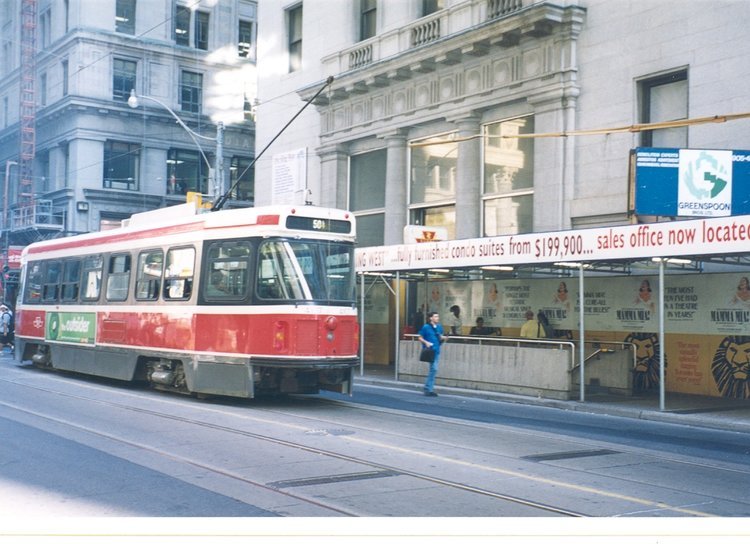

Transit

The City Canadians Love to Hate

Diversity

Employment & Education

In Tolerance

Immigration Policy

After Words

Impressions

[Ron Soskolne] “People from the States used to come here and say, ‘My god, you can eat off the streets.’ And now people look at it and say this is worse than most American cities, in terms of the level of upkeep of the public space.”

[David Miller] “Toronto can no longer honestly claim to be the city that works. I think the decline probably started 20 years ago.”

[John Barber] “The growth of the city has made it unmanageable. It’s still exciting; it’s much more exciting than it ever has been. But it’s also turned into a bit of a wild ride. And we’re having to grow up to that second level of thriving amid chaos that you see working well in places like New York.”

[James Spearin] “They’ve brought too many people over here, too many immigrants into the country.”

[Andrew Pyper] “'I’m hearing more sirens, I’m seeing more non-white people on the street.’ Yeah, I guess that’s out there, in a kind of thoughtless, barroom, hyper-conservative response to terrorism kind of way.”

[John Barber] “The world out there is so different from the world in here, and most of them just don’t know. I have friends who come from other cities and they say, 'Is this what’s Toronto’s like now?’ Nothing prepared them for it. Because it’s so different from any part of the country, just so completely different.”

[Arsinee Khanjian] “It is an absolute necessity to understand who we are and who the other is and what their history is as a positive step towards building a new society.”

The City That Worked

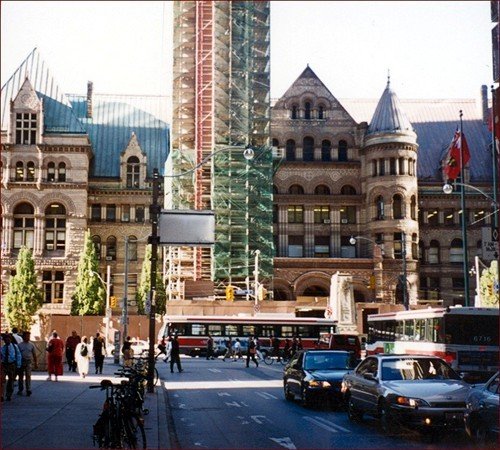

The intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets in bustling downtown Toronto. Thousands converge on the intersection every day – by car or streetcar, subway train, bus, bicycle or by foot.

Former city planner Ron Soskolne: “Yonge and Dundas is regarded by most people as the center of the downtown core, from the point of view of public life, public activity. During the last 20 to 30 years there’s been a process of the various activities moving away from the street and the result being that the street went into somewhat of a downward spiral.”

Now, with a new public square soon scheduled to open and talk of construction beginning this winter on a long-delayed redevelopment project, lower Yonge Street is being slowly transformed.

But Yonge Street is only one example of urban decay in downtown Toronto; the city is ailing and no one can miss the symptoms.

Ron Soskolne: “You have to understand [that] this is a city that up until 10 years ago didn’t perceive itself as being susceptible to this kind of urban decay.”

University of Toronto Professor James Lemon authored a 1982 essay on Toronto in which he described the many reasons why Toronto was then so different from comparable U.S. cities that it “could conjure up the alternative image” as the “city that worked.”

Globe and Mail columnist John Barber:

“I don’t think that those clichés ever really captured the full reality. And even when it was the 'city that worked,’ it depended on what you were looking at.”

Lemon looked at a whole range of differences, including Toronto’s “greater cleanliness, its relative freedom from crime, its efficient public transit, and the distinctive social character of its inner city and its suburbs.”

Lemon wrote the piece at a critical moment when American cities like Philadelphia, New York and Chicago were reaching low points in a long process of postwar decline. But Philadelphia, New York and Chicago have rebounded dramatically in the years since Lemon’s piece was published. And Canadian cities like Toronto have increasingly been turning to American models to restore their diminished luster.

[David Miller] “I think the decline probably started 20 years ago.”

Toronto City Councillor David Miller: “We took for granted that we were a city that knew how to plan. We were confident in ourselves, in simple things: we had clean streets. Politically, people started fighting around the edges, instead of thinking of where is the city going to be in 20 years? People have just now woken up and said, 'Wait a minute, our planning hasn’t worked; how are we going to deal with that?’ There’s lots of things you can cite in the city you see everyday and it’s not the kind of city it could and should be.”

Homelessness and a shortage of affordable housing are two of the most pressing issues facing Toronto. The rapid growth of the city over the past two decades has only magnified these problems.

Immigration from the developing countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America accounts for two-thirds of the city’s recent growth. The 1998 amalgamation of Metro Toronto’s six previously municipalities (of Etobicoke, York, North York, East York, Scarborough and Toronto) into one “mega-city” further swelled the population of the city to 2.4 million residents, creating overnight the fifth largest city in North America.

The economic misfortunes of the early '90s also proved more tenacious in Ontario than elsewhere on the continent, contributing to a political backlash that rejected the traditional welfare state in favor of tax and spending cuts.

With the province downloading debt and services to the to the city, amalgamated Toronto teeters on the edge of insolvency. The Toronto Transportation Commission, the TTC, is starved for cash. A multibillion dollar infrastructure deficit looms. The city has reportedly fallen 10 years behind in its plans to repair roads and bridges. Fewer public works employees are keeping Toronto’s streets and parks clean.

So can Toronto still claim to be the city that works? Writer and Toronto resident Andrew Pyper:

“Well, to mind it’s a city that still works relative to a lot of other cities that I’ve visited on this continent or the European continent. Having said that, that’s a pretty low threshold in many respects. Can it make the claim of the 'city that works’ in some kind of special, noteworthy, follow-this-model sense? I’d say no. There’s just too many quite palpable, visible walk-by examples of it not working.”

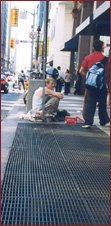

One of the most visible walk-by examples of Toronto’s decline is homelessness.

The Homeless

City officials estimate that 6,000 people are now homeless in Toronto – double the number of a decade ago. Two decades ago homelessness was virtually unknown in Toronto.

Councillor David Miller: “I started working at my former law firm in 1982 as a summer student. There was one homeless man who lived downtown. He lived in a city-owned parking lot at King and University. That was 20 years ago. So I’ve watched with my own eyes – because I’ve either been a lawyer or a Metro or City Councillor; I’ve been downtown the whole time – I’ve watched the homeless population multiply.”

[Andrew Pyper] “Oh, definitely the homeless population has increased. But why in the face of an increasing homeless population has there not been anywhere near an adequate political response? I think most of that blame can be delivered to Mike Harris’s doorstep.”

Mike Harris, “Mike the Knife,” golf-pro-ski-instructor-turned-politician, Conservative party leader for five years, Ontario premiere for another seven. Harris swept into office in 1995, architect of the so-called Common Sense Revolution.

Pyper believes Harris’s policies both accelerated and neglected the growth of the homeless population in Toronto.

[Andrew Pyper] “His values, his world-view is very much in step with the affluent middle- to upper-middle-class suburbanites [that is] the largest voting bloc in the province. So I think he’s developed or encouraged a political culture of getting on with business, of cutting the crap: where the crap is sympathy for others; where the crap is taxes; where the crap is people who kind of irritatingly knock on your window as you idle in your minivan and ask for money. So there’s a level now of acceptance of being impatient with those irritating and slightly ugly social problems that are growing.”

One thing the Harris government cannot be blamed for is creating “ugly” social problems like homelessness. By the time Harris grabbed the provincial reins in 1995, the numbers of homeless in and around Toronto had already swelled to unprecedented levels.

Many were victims of the new economic reality brought about by Canada’s most prolonged recession in 60 years. And no province was hit harder than Ontario, which by 1993 had lost 80 percent of the manufacturing jobs that disappeared in Canada during the downturn.

At roughly the same time, nearly half of the country’s 1.6 million unemployed lived in Ontario, and a third of those lived in Metro Toronto. Free trade took much of the blame.

Free Trade

The Canada-U.S. free-trade agreement, or FTA, went into effect the 1st of January, 1989. By December, layoffs and plant closings were adding up, and free trade came under heavy fire.

High interest rates, high taxes, the high dollar, the U.S. recession and global competition were also cited as culprits, but none resonated as emotionally as free trade.

[John Barber] “For this regional economy that was very traumatic.”

John Barber: “It had been built up basically behind a wall of tariffs, and Toronto’s role was to serve the national market, if you will, supply it with manufactured goods. Free trade changed all that radically. And we became rather than the economic capital of an east-west country, we became another regional node in the North American economy – a fundamental change. And 200,000 jobs disappeared.”

[David Miller] “In Ontario in '88, '89, '90, and '91, every single day a factory closed.”

Councillor David Miller: “Overnight, we went from thriving, because our industries were protected by tariffs, to being a rust belt, overnight. One of the political dynamics of that was we elected a very conservative government in 1995.”

And it was no ordinary election. The Progressive Conservatives, led by Mike Harris, took back the majority they had surrendered 10 years earlier, winning 82 of the legislature’s 130 seats.

[Sound clip: Mike Harris victory speech]

John Barber: “We had this huge reaction in which this really tough-minded right-wing government took hold and went just as far in the other direction, in terms of cutting spending. So we’ve been to both extremes in the past decade. And now I think the general consensus is that there has to be more spending, that the balance is just not there and that we’re falling way behind.”

But Mike Harris presided over a dramatic economic boom that produced half a million jobs in the province during his first term as premiere. An impressive rebound in Ontario’s beleaguered manufacturing sector figured as one of the leading catalysts of the upturn.

But economic prosperity came at a price.

Just as the city was pulling itself out of recession and adapting to its new role in the North American and global economies, “mega-city” was imposed.

[Sound clip: news report]

Mega-city

The Ontario Conservatives argued that amalgamation would trim government expenditures by streamlining bureaucracy and offering single, efficient services like fire, police and garbage collection.

Andrew Pyper: “I think it was an instrument that was sold to the people of Ontario and Toronto as cost saving; this will be more efficient. 'And it’s indifferent. This isn’t a political move; this is just good sense.’ And 'streamline’ – words like that.”

[Sound clip: protests]

The government introduced the bill in December 1996, initiating a bitter four-month clash with a motley opposition that used demonstrations, general strikes, popular referenda, legal challenges, and an extraordinary legislative filibuster in an unavailing effort to defeat the bill.

Globe and Mail city columnist John Barber: “As a columnist back then I was very, very much against the mega-city. I thought it was a terrible political initiative that would be an expensive boondoggle and would not accomplish its goals of saving money or making government more accountable. And, you know, I hate to say that I’ve been proven right beyond my wildest dreams. I mean, everybody knows it’s been a disaster.”

Nearly four years after its introduction, the $275-million project had yet to produce any savings. One source reported that administration costs in the new City of Toronto had ballooned to 13 percent of the total budget. This meant that the six municipalities mega-city replaced were actually more efficient.

John Barber believes mega-city has turned Toronto’s municipal government into a negative force. “I mean, they just haven’t been able to move forward in any way; it’s really unfortunate. Just the difficulty of reorganizing the city has absorbed the city government’s energies.”

The logistics of mega-city have been formidable. Six sets of complex city bylaws would have to be unified. And the new City of Toronto would have to square wage differences between employees of the former municipalities. That task has proven especially thorny, with one public-sector labor crisis following another.

Last summer, 25,000 municipal employees, including the city’s 600 garbage collectors, walked off the job, palpably – and rather pungently – illustrating the rigors of administering the mega-city.

[Sound clip: news report]

The many critics of amalgamation believe that such negative consequences could have – and should have – been avoided. Reforms were certainly needed, but political considerations came too conspicuously into play.

Councillor David Miller: “Amalgamation probably wasn’t the best idea in the first place, but it was very rushed and politically motivated. They didn’t like the government. The government in Toronto was perceived to be left wing. So they decided they wanted to get rid of it. No thought, no planning. And then they proceeded to cut all sorts of funding that the city had and give us responsibilities we didn’t have in the past, all of which made amalgamation even harder because there was no money to go around.”

Amalgamation has also produced a new political dynamic. In the amalgamated City of Toronto, most of the population resides outside the downtown core. Andrew Pyper believes that this has allowed for the government of Ontario to “neglect without apology” problems distinct to downtown Toronto.

“It was a brilliant tactical turn by the Conservatives because it has allowed them to treat Toronto like this block of similarly situated communities. And, of course, it’s not.”

[Kyle Rae] “And that’s part of the problem of amalgamation.”

Toronto city Councillor Kyle Rae: “You often get political leaders or heads of departments thinking that all parts of the city should be treated equally, when, in fact, the city is not the same across the municipality. There are concentrations of residents, which means you have to have different levels of service.”

One of the most glaring deficiencies in public services has been expressed on the litter-strewn streets and sidewalks and in the parks and public spaces of Toronto.

Professor James Lemon in his 1982 essay noted that public works employees swept city streets daily. And it showed. Toronto’s streets and sidewalks were known around the world for their meticulous upkeep.

Nearly 20 years later, downtown litter pickers were out twice a day and street sweepers every night, but they weren’t keeping up.

(In 2000, the mayor of Toronto launched a $2.3-million cleanup campaign, simply called “Clean Toronto. "Hundreds of new garbage containers appeared on the city’s street corners; 40 students were hired as litter-pickers; 13 new bylaw enforcers were put on the streets; 12 new sidewalk litter vacuums were acquired. Still, the trash piled up.)

Last year, Toronto’s Clean City Task Force spent $20,000 on a "litter audit,” paying work crews to place the city’s trash into categories rather than containers, and simply confirming what most Torontorians already knew: the city was a mess.

Downtown Councillor Kyle Rae says his office receives at least one complaint a week about dirty streets and badly maintained parks. He says the complaints began right after amalgamation.

[Kyle Rae] “I think with amalgamation the number of staff were released from the city, and I fear that some of it was in that area in public works. I don’t think there were as many litter pickers in the other parts of the municipality as there were in the inner city, because you recognize in the downtown you’ve got a high incidence of littering and you need to be more vigilant.”

Ron Soskolne: “The city has generally been screwed over the last seven, eight years in terms of the amalgamation that happened here and being really starved for resources. It was given huge new responsibilities and really no money with which to deal with those things. So the standard of maintenance of public space, for example, just went off a cliff.”

[Kyle Rae] “Guests who are coming in from outside, they still say, 'This is cleaner than my town.’ But they say, 'This is not as clean as it was five years ago.’ So they do still think it’s cleaner here in Toronto than it is in New York or Chicago or L.A. But they don’t think we’ve been maintaining our cleanliness.”

But Kyle Rae, for one, won’t give all the blame to politicians.

[Kyle Rae] “People often like to point to the city that you’re not doing the job, when, in fact, the City of Toronto does not put the litter in the streets; it’s the public that puts the litter in the streets. And there seems to have been some sort of attitudinal change that’s occurred, where people no longer think that they need to be part of the solution of keeping this city clean, that there’s something drastically wrong in the attitude of the people who are coming into the downtown.”

A retired architect who came to Toronto from Romania 32 years ago has observed a steep decline in the cleanliness of the city’s streets and sidewalks. He believes the “change of attitude” can be attributed to recent immigration to the city.

[Romanian man] “I don’t want to sound racist, but there are people coming from poor countries; they’re not educated; they’re probably used to a different lifestyle. They don’t keep the place keep clean. When I came first, it was clean. And now it’s just garbage.”

Of course, many residents of Toronto would reject that argument as garbage.

Still, with 10,000 new downtown residents since 1996, it’s undeniable that the growth of Toronto has made the city more difficult to manage and maintain. John Barber believes the growth of the city has, in fact, made it unmanageable.

[John Barber] “Growing pains are very obvious here. You know, what worked for a quite compact city of 2 million or so with a very strong core doesn’t work for an urban region of 4.5 million with tremendous new demographic social strains.”

One simply cannot talk about Toronto’s new demographic social strains without talking about immigration. Fully two-thirds of Toronto’s population growth now comes from international immigration.

Without immigrants, more people would be leaving Toronto than arriving. Ontario alone attracts more than half of all immigrants to Canada. And about two-thirds of them settle in Toronto. Another 25 percent of immigrants who originally settle elsewhere wind up in Toronto after the first year.

John Barber: “You know, the ethnic demographic melting-pot effect of this place right now is really, really dynamic. Without saying good or bad, it’s very impressive – it makes an impression! And that seems to be working pretty well. I think that works, although there are, again, very worrisome signs – about income distribution, for instance.”

Poverty

Toronto’s immigrants are losing ground. The disparity between immigrant and non-immigrant incomes is growing. Poverty rates among certain ethno-cultural communities are escalating.

Ethiopians, Afghans and Somalis confront poverty rates approaching 70 percent. Approximately half of Toronto’s Aboriginals, Jamaicans and West Indians live in poverty. Vietnamese, Iranians, Tamils and Sri Lankans live, by one account, in “'severe disadvantage,’ with high unemployment, low-skill jobs, low education and high rates of school drop-outs.”

Overall, nearly one in four Toronto residents now lives in poverty, with the rate of poverty increasing a startling 67 percent between 1991 and 2001.

Meanwhile, the number of children living in poverty is also growing. In Toronto’s poorest neighborhoods, child poverty rates have climbed 35 percent since 1996.

And these aren’t an isolated handful of city neighborhoods. More than 100 Toronto neighborhoods, spread across the city, endure poverty rates of more than 30 percent. That number jumps to 60 percent in the very poorest neighborhoods.

[Andrew Pyper] “Not only have the poor gotten poorer very quickly over the last few years, but the poorest are suffering at a higher level than they were even five years ago.”

Housing

With the average two-bedroom apartment currently hovering around $1,000 rent per month, circumstances are especially difficult for low-income renters in Toronto. Close to half of the city’s residents now spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. And there is a critical shortage of affordable housing, with city waiting lists containing up to 90,000 names in recent years.

In fact, Toronto has been losing affordable housing, as older apartment buildings are demolished and high-priced condominiums spring up in their place. Since 1995, more condominiums have been constructed in Toronto than any other form of housing.

Downtown Toronto construction sites; the billboard reads: "The Condo Life: Where the Excitement Never Ends"

Last July, residential construction hit its highest monthly level in 13 years, registering a 50 percent increase from June. Condominium construction accounted for much of the upturn.

As private rental unit construction continues to lag far behind, condominiums, according to one source, “are now the most significant source of new rentals in the Greater Toronto Area. The trend has already begun slowly pushing Toronto’s vacancy rate up – and the cost of rent down.

John Barber: "I tend to look at the housing construction in the central area as being a net gain. I mean, it’s good in itself, but it’s not the whole picture. I really do think affordable housing and mixed environments is very possible. We’ve done it in the past and we can continue to do it in the future, and we should really get on with that.”

City Councillor David Miller agrees. Miller, a champion of mixed-income housing, seeks to check the influence of private developers but considers it a mistake to staunchly oppose any new development.

[David Miller] “The result when you do that is way worse than if you try to help guide the development process with really good policies and rules about things like parks, sidewalks, streets, density. Development is an important tool to help the city grow well if it’s guided right and if citizens have a real say in how it’s going to shape their community.”

That’s what the authors of Toronto’s official 30-year plan hope.

Toronto’s 30-Year Plan

Three years in the drafting, amalgamated Toronto’s first official plan replaces the plans of Toronto’s pre-amalgamated municipalities.

Kyle Rae: “For three years the staff have worked on this. There have been 183 meetings with resident groups. It’s been a Herculean effort by [the city’s] planning department to weave together the old city – the prewar city of Toronto – and the new suburban parts of the city into one official plan. And I’m very pleased to be an advocate for it.”

Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman has been one of the most outspoken advocates of the official plan. Lastman has promised that the plan will “protect every community in Toronto.”

Indeed, neighborhood protection is a hallmark of the 30-year plan. Under the proposed plan, 75 percent of the city – including neighborhoods, parks and open spaces – will essentially remain the same.

With the city expected to add 1 million new residents during the next 30 years, the plan proposes to focus population and job growth in the remaining 25 percent of the city. (That area includes downtown and the central waterfront, as well as parts of Scarborough, North York and Etibicoke.)

The idea is to create “hubs” of residential and commercial activity in high-density areas where people have easy access to public transit.

Councillor Howard Moscoe: “The underlying basis of the official plan is a good idea. I think basing the official plan on public transit is a necessity. I think planning for growth is absolutely essential.”

Councillor David Miller: “It’s an environmentally friendly vision; it’s a people-friendly vision; it’s a transit-friendly vision. But some groups of citizens are nervous, because they think it means their neighborhoods will get bulldozed and just replaced with apartment buildings, which is what happened in Toronto in the late '60s and early '70s because there was just wild development.”

Those suspicions are based on the plan’s lack of density and height restrictions for new buildings. Last summer, Councillor Moscoe took his concerns directly to constituents by circulating a newsletter. Moscoe warned readers that stable residential neighborhoods would be “wiped out” under the proposed plan.

Moscoe was loudly criticized. “What Howard is doing is stupid and dishonest,” said one councillor.

[Howard Moscoe] “I’m sure that anyone who disagrees with me has always said that, but so what? If I had to exaggerate, I’d rather exaggerate in favor of my community rather than in favor of the academic niceties of the planners. So I don’t have any apologies for trying to start up a discussion in my community.”

Another point of contention stems from the plan’s emphasis on public transit. With the city’s $1.8 billion debt, critics of the plan wonder where the money to pay for new transit lines will come from.

David Miller is one of council’s most resolute supporters of public transit.

[David Miller] “The reason it’s important from a city-building perspective is [that] transportation is critical. I mean, if you don’t have good transportation, the city doesn’t live and breathe. And you end up being a place that is governed by what works for cars, instead of governed by what works for people.”

And putting the brakes on sprawl is one of the main priorities of the 30-year plan. City planner Paul Bedford believes that Toronto must attract 1 million people to avoid a population explosion in the region.

Bedford warned two years ago that without a dynamic plan to entice new residents to Toronto, another 2 million people would settle in the outer reaches of the Greater Toronto Area during the next 30 years. And public transit would be further marginalized by car-dependency.

Even if sprawl is contained, Greater Toronto has already grown well beyond the public transit system’s ability to serve its residents.

Councillor David Miller: “The flaw in the transit system is, first of all, that the suburbs were built for cars, so they’re not of the densities that support a transit system. So the people from the suburbs come into town in their cars; they do everything in their cars. Second problem is our transit system is built to serve downtown. We have to think about the city as not just getting people downtown, but moving people around. And the economy’s changed.”

David Miller insists that public transit needs to be closely related to planning. But whether or not the political will exists to implement such measures, the question of cash is a crucial one.

[David Miller] “Until this year under the Conservative government in Ontario, they didn’t fund transit. We yelled and screamed enough. They now fund a third of our capital program; when I was elected they funded 75 percent. I’ve only been elected eight years.

"The reason this all matters is because all of our funding comes from the property tax. We don’t have a city income tax or city sales tax or a hotel tax, or anything like that. In the property tax, when the economy grows it doesn’t grow; you don’t get any more revenue. At every level of government, when the economy grows, you get more revenue. We don’t. In the last 10 years, federal and provincial governments’ revenues have doubled and ours have been flat.”

As Ottawa and Queen’s Park have cut provincial spending and downloaded services to cities, no change has been made in the way those cities generate revenues. This defect is perhaps a symptom of a larger issue at work: as Canada’s cities have grown, their political clout, some say, has not.

David Miller: “We’re now Canada’s sixth largest government. It gives us the opportunity to be enormously influential. But we’re still governed as if we’re a small town. Literally the laws that govern Toronto, although they’ve been tinkered with over the years, but the laws that currently govern us were basically written in 1867. And Toronto then had a population of 35,000 people.”

The City Canadians Love to Hate

There may still be another, less tangible factor in play, an age-old rivalry that pits Toronto against the nation at large.

Urban scholar Jenny Burman: “In a national framework, Toronto is the city that you love to hate, if you’re outside of Toronto, because it dominates the news often. There’s a daily newspaper, the Globe and Mail, which people refer to tongue in cheek as 'Toronto’s national newspaper,’ because it claims to be a national newspaper but it’s very much Toronto-focused.”

Novelist Andrew Pyper recently attended a small Ontario town’s book festival. Asked by a fellow writer where he “lay his laptop,” Pyper replied, “Toronto.”

[Andrew Pyper] “So, how are you enjoying your visit to Canada?” the other asked.

It’s an old joke. But Pyper, himself the product of a small-town Ontario upbringing, thinks the anti-Toronto sentiment the joke expresses is becoming less and less humorous. In fact, Pyper has become quite distressed by the perceptions – or misperceptions – other Canadians have of Toronto.

[Andrew Pyper] “It’s perceived as the unfair, disproportionate recipient of federal dollars – goodies – that people who live here are arrogant, self-involved, ignorant and even hostile to those in the hinterland, and that we’re all rich, that we’re all sort of here giggling, à la Richie Rich, on our sort of bags of gold coins.

"Those perceptions – we could argue about their validity as observations; but more important than their truth-value is their prevalence, which has led to widespread political neglect. It’s very hard to stand up right now in Canada and say, 'Toronto’s in trouble, it really needs help.’ I think the level of sympathy outside of Toronto would be next to nil.

"So it’s not a particularly favorable climate for sober exchange of data [on Toronto’s decline] when knee-jerk prejudice is more convenient.”

No matter how steep the decline, Pyper believes it will take a long time to “destabilize” those perceptions of wealth, greed and insularity.

As Toronto has adapted to its new role in the global economy, the chasm may have only widened. The Globe and Mail’s John Barber contends that Toronto is now detached from the national economy in a “fundamental way.”

[John Barber] “The new Toronto has nothing to say, really, about Canada in that same way. The attachments of the new Toronto are global, entirely global. Nobody from Canada comes here anymore. It used to be that most of our immigration came from within the country. Well, they don’t come here at all anymore.

"People who come here [now] come from other parts of the world, and they maintain their relationships with other parts of the world. And there is something that is quite different happening that removes Toronto from the national identity in a way that we haven’t come to grips with yet.”

Diversity

By several statistical measures, Toronto is now the most ethnically diverse city in the world. Ten years ago, 42 percent of people living in Metro Toronto were foreign born, double the percentage of foreign-born living in that legendary ethnic melting pot, New York City.

Today, foreign-born residents make up roughly half the population of Toronto. And where the foreign-born in Toronto used to be overwhelmingly white, well over half the city’s immigrants now come from Asia and the Caribbean.

The Armenian-Canadian actress Arsinee Khanjian, a resident of Toronto, was raised in Beirut. She moved with her family to Canada when she was 17.

[Arsinee Khanjian] “This is an actively welcoming country for all kinds of immigrants, refugees from around the world. I mean, it’s probably one of the only countries that still has that opening up to the rest of the world, for whoever wishes, if they can, for either economic reasons or for political reasons, or because they would love to live in the Canadian society to come here. So we are every day in this situtation where we encounter people from elsewhere.”

Omar Marquina recently arrived in Toronto from Mexico City.

[Omar Marquina] “It’s a shock trying to see all these multi-cultural areas because in Mexico you can see everybody’s alike. But here you can see many countries, peoples. It’s kind of a shock, but I like it.”

The people of Toronto come from 169 countries. In the city’s Jane-Finch neighborhood alone, more than 72 languages and dialects from 115 countries are spoken. By one estimate, there are close to 500 ethnic groups in the city counting 5,000 residents or more.

John Barber: “Well, I think the most amazing thing about Toronto now, at the beginning of the 21st century, is this ethnic and racial dynamic. Nobody’s ever really been here before. I mean, New York 100 years ago was kind of like this, but I don’t think there was as great a variety of races and languages that were spoken even then.

"And, you know, this is part of a worldwide phenomenon, and we’re way, way out there, in terms of how to establish a functioning multi-racial, multi-ethnic, completely globalized society. That’s really exciting.”

[Jenny Burman] “One of the reasons that I really love Toronto is the promise of Toronto.”

Jenny Burman:

“It has the real potential to be a kind of city of refuge. It has a lot of impressive services for immigrants; it has a lot of established third-, fourth-, fifth-generation immigrant commiunities. So it really does have a cosmopolitan flavor that I think can make it a very inviting place for people to move to.”

[Omar Marquina] “Yes, it’s been great, because I think Canada has had a lot of immigrants for a while. So they have several programs free of charge that will help you to settle in all kinds of areas – housing, jobs, people, everything related. And it’s helped us because we were new; we don’t know how to do it if they don’t have these programs.”

Such programs can certainly ease the transition for those who take advantage of them. But what draws so many immigrants to Toronto in the first place?

Thirty-four-year-old Omar Marquina has lived almost his entire life in Mexico City. Educated as an electronic engineer, Marquina left his job as a telecommunications manager for a Mexico City-based retail company to immigrate to Canada.

[Omar Marquina] “I had two main reasons in importance of order: I would like to find a more healthy place to live, because my wife and I are planning to have kids; the second is to be away from violence.”

Nazir Ahmed also cited violence and crime as reasons to leave his native country.

[Nazir Ahmed] “In Bangladesh, except one thing, everything is the best; I think the best in the world – only one thing: the law and order situation.”

So why Canada?

[Nazir Ahmed] “I heard that Canada is highly economically developed and that life is high – high standard of living. After coming here, I see the living standard is higher, but earning is very tough.”

Employment & Education

Educated at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Nazir Ahmed worked 13 years in Bangladesh as a civil engineer. Currently employed as a part-time cashier in a Yonge Street convenience shop, Nazir expected to find work in Canada compatible with his training and experience. He chose Toronto for its favorable job market.

[Nazir Ahmed] “When the immigrants go for doing job they get job lower than their expectation. Nowadays, most people [who] come here are highly educated. But they don’t get any job [at] their level of expectation. So they are doing small jobs like in restaurant, this convenience store. But this is not their expectation. So they are frustrated.”

[David Miller] “One of the problems we have in Canada is we have a terrible system for evaluating foreign-trained professionals.”

Councillor David Miller: “People get recruited as a teacher or a doctor and they get here and can’t practice their profession. You know, so the stereotype of people with Ph.D.s driving cabs is somewhat true in Toronto.”

[John Barber] “There’s a demand for low-cost labor; we’re living on it.”

Again, John Barber:

“Basically, we sell citizenship for the opportunity to have people who are going to work minimum wage in our economy. It’s a pretty – on some level it’s a pretty cut-and-dry arrangement. And business knows that it needs those workers, so there’s a lot of political support for [high] levels of immigration.”

But when those workers are highly educated professionals, clearly there’s a problem. Last May, the National Post noted that thousands of doctors have immigrated to Canada, but “face huge restrictions in terms of entering medicine or getting evaluated.”

In November, Ontario’s Conservative government announced (a $36.4-million-a-year) program to license 650 foreign-trained physicians by 2007. The program, of course, will do nothing to aid the vast majority of Toronto’s underemployed and unemployed immigrants.

[Nazir Ahmed] “This is my realization: a lot of people will come here; the government should tell them, 'There is no job for you.’ From my one-year experience, the Canadian government need labor, not highly educated people. It’s my guess, what I’ve seen.”

Frustrated with his lack of success, Nazir Ahmed described himself last September as “somewhat pessimistic, but not giving up.”

Not having experienced the same frustrations as Nazir Ahmed, newcomer Omar Marquina is decidedly more optimistic. But he’s also realistic.

[Omar Marquina] “Well, I probably will have two choices: [first] to do like a 'survival job’; that is working in some[where] else that is not in my field; the second will probably be in my field but at a basic level, entry level. So [I] will probably have to move up. So that’s the two options. The better will be getting my field in my previous position.”

Eventually, Marquina hopes to get a job more challenging – and more lucrative – than the job he left in Mexico City. He knows it won’t be easy.

[Omar Marquina] “What has to be done is to be positive and to be willing to do it. Even if you get a job, a basic entry job, don’t stop, keep searching, because you can find a good job. I’m really sure about that.”

In coming to Canada, Marquina brought with him more than a positive attitude. Anticipating a competitive job market, Marquina completed the necessary coursework to ensure his academic standing in Canada. He even took a job washing dishes.

[Omar Marquina] “I went for training for one day. I stayed there from five [p.m.] till 1:30 in the morning, just wondering what will be the worst-case scenario, where I could get if I don’t find a better position.”

Arriving in Toronto last August, Marquina soon began familiarizing himself with the public transit system, improving his English skills, attending job workshops and simply meeting people.

[Omar Marquina] “You have to be out of your house; your house is your enemy when you are an immigrant.”

[Sound clip: labor protest]

For months, the workers at the Quality Hotel on Bloor Street have been protesting unfair treatment by management. One of the organizers of the protests is Rommel Favila, a Filipino hotel employee who has been in Toronto for seven years.

[Rommel Favila] “The issue is all about wages and the 18 rooms that the room attendants are cleaning right now. In here at the Quality Hotel, our room attendants are doing 18 rooms, and if they don’t finish the 18 rooms at 5:00, they’re gonna ask you to swipe out your card, sign out your paper and they’re gonna ask you to go back to your unfinished work. And this is unfair labor practices.”

In September, the Hotel Employees, Restaurant Employees Union Local 75 was calling for a boycott of the hotel until a fair agreement was reached between the workers and management. Workers had voted nine days earlier to “take any action up to and including a strike, if necessary.”

In late August and early September, University of Toronto researcher Richard Fung noticed…

“…there were a number of strikes at hotels. And I remember passing the picket lines, and those picket lines were mainly immigrants of color – Filipinos, black people, Chinese, South Asians. And those are the people who do this kind of work that white Canadians don’t want to do. There’s a kind of trans-national working class, a kind of browning of the working class.”

Of course, immigrants don’t necessarily want these jobs either. They simply have fewer choices.

[Rommel Favila] “It’s hard to find another job, so I keep working in here. But as I experience working here they’re forcing you to work, work and work.”

Before coming to Canada, Favila had worked as a legislative staff officer for the Congress of the Philippines. He left that job to join his wife, who had already settled in Toronto. There were other considerations as well.

[Rommel Favila] “I wanted really to come to Canada, because when I studied Canada – history, the way of life, the economics, politics – compared to my country, it’s much better, because if you have kids, you want to raise your kids in a good environment.”

Rommel Favila’s standard of living has improved since coming to Toronto. But that improvement has had its limits.

[Rommel Favila] “Compared to the Philippines, life here is much easier, because here you have all the liberty. But here I cannot use my education from the Philippines because right now I didn’t go to school here in Canada.”

For his education to be recognized, Favila will need up to a year of schooling in Canada. But attending school for even six months has so far been unmanageable.

[Rommel Favila] “In the first place, I don’t have enough money. And the second issue is I’m busy working two jobs, so that’s why I don’t have enough time to study. But right now I am planning to resign my part-time job and to go back to school because I want to uplift my life.”

Education is only one factor limiting job opportunities for immigrants. Work experience is another, including for those, like Nazir Ahmed, whose education is recognized by the government.

[Nazir Ahmed] “One type of reply I got from everywhere [is] that your experience is pretty good, but right now we are not able to take you in our office, so wait for later.”

Later, unfortunately, means when the applicant has obtained so-called Canadian experience.

Having only begun his job search, Omar Marquina has already encountered this obstacle.

[Omar Marquina] “They have been asking for the Canadian experience. Really, I haven’t found somebody who can tell me what actually the Canadian experience [is]. They can say, 'You have to work in a Canadian company,’ that’s it. As long as it’s Canadian, it’s Canadian experience.”

Victoria, who preferred not to use her real name, believes the demand made by employers for Canadian experience is both unnecessary and unfair. Victoria’s mother had been a bank teller in Guyana for almost 10 years. Arriving in Canada in 1972, no bank would hire her.

[Victoria] “It’s all about having Canadian experience. I don’t understand how someone doing the same job in another country – if anything, based on her experiences that she’d have there, she could accept whatever training they could offer and add that to her abilities. I don’t see how that that’s a deficiency.”

David Miller’s British mother faced similar obstacles.

[David Miller] “When my mum came in 1967 – came back to Canada; she had already been here and taught – she came back as a teacher, and they told her she wasn’t qualified. It was just absurd. It’s been going on for at least 40 years. So it’s time to fix that problem.”

But not everyone thinks the system is unsound. One letter to the editor published in September by the Toronto Starchastised an Indian immigrant for having come to Canada “thinking that his professional credentials and career accomplishments would be immediately recognizable and transferable. This is a ridiculous assumption,” the author of the letter concluded.

Meanwhile, civil engineer Nazir Ahmed gains “Canadian experience” cashiering in a downtown convenience shop.

In Tolerance

One thing neither Nazir Ahmed nor Omar Marquina have encountered in their time in Toronto is blatant racial or ethnic discrimination. The city’s slogan is “Diversity is Our Strength.” For the most part, it rings true.

[David Miller] “I think it’s one of the greatest gifts Toronto has.”

Victoria recently returned to live in Toronto after being away for seven years.

[Victoria] “It’s funny; my very first week back here I was walking down the street and there was a school bus going by, and there was a Muslim woman – and I knew she was Muslim because she had the full burka on – and she was driving a school bus. That instant was really great for me. I just thought: this is truly multicultural; this isn’t tokenism anymore. And that’s exciting.”

Muhammad, 15, has lived with his family in suburban Woodbridge for seven years. His father owns a Pakistani restaurant on Gerard Street in Little India in old Toronto East. Originally from Pakistan, Muhammad, a self-described Persian-Oriental-British-Canadian, has not encountered racial abuse.

[Muhammad] “I have no problems at all so far.”

[Stephen Miles] “And has that been the case as long as you’ve been in Toronto?”

[Muhammad] “Yes. Nothing happened so far.”

If incidents of overt discrimination are relatively rare, there is evidence to suggest that some Toronto residents are skittish about the relentless flow of immigrants into the city.

Last September, the Toronto Sun, a tabloid-style newspaper with avowedly conservative politics, ran a front-page headline declaring, “Canadians Want to Clean Up This Immigration Mess.”

The Sun published the results of a nationwide poll it conducted in August that found that 35 percent of Canadians wanted immigration laws and quotas “tightened significantly,” while another 34 percent wanted them “tightened somewhat.” The Sun noted that only 5 percent of those questioned felt that restrictions on immigration should be relaxed, while 21 percent were content with the status quo.

David Miller: “I think there are some tensions, but I think if you examined those polling numbers, you’d find that predominately the people who are really most concerned about immigration are people who are a little bit removed from it in the smaller towns and don’t see it as much. That’s my sense.”

Toronto resident Andrew Pyper agrees. He thinks the sentiment the poll reveals …

“… i.e., we’re letting in too many of those 'brown people,’ is a sentiment that would be mostly held, I think, in places that, oddly enough, probably haven’t experienced that much immigration in their communities.”

Pyper says he just doesn’t hear much about current immigration policies being a mess.

[Andrew Pyper] “I don’t hear it here where "here” is really, you know, downtown central Toronto. It would be an almost impossible position to maintain, given that if you lived in central Toronto, you’d be talking quite literally about your neighbors, which doesn’t, of course, stop racists from expressing racism, but it would be hard to sustain.“

James Spearin sells Toronto Street News for the homeless on Queen Street East in the Beaches area of Toronto. While the Beaches neighborhood is not downtown, it’s not far removed from it. And the ethnic composition of the Beaches approximates that of the city at large, with a slightly larger proportion of Chinese residents. Chinese, in fact, is the second most spoken language in the Beaches.

Still, the proportion of residents reporting either British or Canadian ethnic origin in the more affluent of the Beaches’ two wards is three times that of the larger city.

Spearin is 49 years old, white, and has lived in Toronto his whole life. He shares the opinion that current Canadian immigration policy has gone too far.

[James Spearin] "Well, I don’t want to sound racist, but I think it’s that they’ve brought too many people over here, too many immigrants into the country.”

Elsewhere in the Beaches, in fact on the beach, Margaret Schuster, a 52-year resident of Toronto who came to Canada from Austria, agreed that Canadian immigration policy was in need of reform.

[MS] “Yeah, I think that would be good, because there are too many people here already.”

[SM] “So you think they should just have restrictions where they cut the numbers?”

[MS] “I think so; yes, I think so.”

[SM] “You just think the numbers, not any certain groups.”

[MS] “No, no. Just the numbers. Less people; yeah, that’s right.”

The Romanian man whom we earlier heard from expressed similar sentiments.

[Romanian man] “I think that there are too many immigrants coming at one time and they don’t have time to adjust to the new place. So …”

[Stephen Miles] “So slow it down.”

[Romanian man] “Yeah. Slow it down.”

While it took little effort to find three Toronto residents who criticized Canadian immigration policy, it would be reckless to conclude that those opinions reflected – and, in fact, confirmed – the findings of the Sun poll.

University of Toronto researcher Richard Fung: “Here papers like the Sun have long had an anti-immigrant stance, and a racist stance, actually – a paper that is read by a lot of immigrants and a lot of people of color. It’s populism. Right? So it doesn’t surprise me that you’d find people on the Beaches who say, 'Oh, yes, we have to clean it up.’”

Victoria agreed.

[Victoria] “I find that there’s a tendency when you immigrate to a place, you secure your family; you make sure that everything’s okay for you. There’s a tendency to forget that there are people coming in the door behind you. Immigrants who make comments like, 'Oh, the city needs to be cleaned up; we should stop letting immigrants in,’ I think it’s about self-preservation. It’s about survival.”

But John Barber, for one, believes that concern with immigration policy is misplaced.

[John Barber] “There’s a dynamic of cultural exchange that no government policy is going to change. I think that people don’t realize that yet, and they still think that immigration is like a set of levers in a special room in Ottawa that you can pull and push and somehow change. To most Canadians that’s a realistic assessment, because the world out there is so different from the world in here, and most of them just don’t know.”

Even with calls to close Canada’s borders, an anti-immigration backlash of any serious magnitude does not seem to be developing – in Toronto or the nation at large.

More typical than the Sun poll is a nationwide survey conducted last January which found that two-thirds of Canadians either believed the country was letting in the right number of immigrants, or not enough.

— Audio continues below —

(In recent years, Canada has attracted upwards of 225,000 immigrants annually. Now the government wants to set a new target - 310,000 newcomers per year, or one percent of the population. One percent is actually Canada’s historic average, but it’s well below the three-percent peak rate of the early 1900s.

Yet even at current levels, no other country welcomes more immigrants per capita than Canada. The U.S., by contrast, admits about half as many immigrants per capita.

But birthrates in the United States have not fallen as steeply as they have in Canada.

Birthrates are especially low in Toronto, Canada’s most populous city. So it’s not surprising that for the first time since World War II, immigration is Canada’s main source of growth. John Barber:

“I think that realistically we’re going to maintain very high levels of immigration. Whether it’s good or bad is kind of beside the point.”)

Immigration Policy

But while the government hopes to increase immigration, new restrictions have been imposed, effectively raising the bar on who gets in – and who doesn’t.

Critics predict that “well-connected, highly educated” people from Europe will be the main beneficiaries of the new policy, meaning that many would-be immigrants from Asia and Africa will be shut out.

Victoria views the policy as part of an ongoing trend. Canada, she says, has “really closed its borders” and been “very selective in who its closed its borders to.”

[Victoria] “Canada is put out there as an all-accepting multicultural country. But the reality is that the immigration policy is very racist and it always has been.”

Last summer, federal Immigration Minister Denis Coderre proposed changes to Canadian immigration policy that would steer a million newcomers to the country’s less populated regions by 2011. With eight out of 10 immigrants to Canada settling in Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver, and half of those settling in Toronto, Coderre set out early last year to rectify those imbalances.

But the solutions he proposed were widely condemned, even drawing comparison to “Soviet-style” decrees.

Coderre’s plan would contractually bind new immigrants to remain in a given location for up to five years in return for Canadian citizenship.

Unemployed Toronto taxi driver James Spearin thinks Coderre’s plan would go a long way toward mending what he believes is Canada’s “immigration problem.”

[JS] “I think they should like spread them out, like make them go to the outer reaches, up north and wherever, where it’s unpopulated.”

[SM] “Where it’s also pretty cold.”

[JS] “Yeah. [Laughs.] That too.”

[Victoria] “Someone coming from a different country who doesn’t necessarily speak English or French, putting them in the middle of a really rural area, there’s nothing there for their children. There’s very little that they have to make them feel like this is their home. And how can you expect people to build something when you’re giving them nothing to build with?”

In October, the Toronto Sun reported that Ontario will be the first province to launch a pilot program, implementing Immigration Minister Coderre’s controversial plan.

After Words

Last October also saw passage of the official 30-year plan. Council voted 34-7 in favor of the plan, with “yes” votes coming from David Miller, Kyle Rae and Howard Moscoe.

Mayor Lastman promised, “This plan is going to protect every community in Toronto.”

But Lastman will exert little influence over that process. The two-term mayor announced in January that he would not seek a third term.

New Democrat David Miller is one of several candidates lining up to replace Lastman. Miller’s priorities include pushing senior levels of government to provide operating funding for the Toronto Transit Commission.

If elected in November, Miller may find that task easier than his predecessor has. In October, the federal government finally owned up to its responsibility in providing for Canada’s cities.

[Sound clip: annual Speech from the Throne, Adrienne Clarkson, Governor General of Canada]

Transit and affordable housing were high on the government’s list of priorities. Of course, the government’s commitment to urban renewal remains to be seen.

At the provincial level, the New Democrats and Liberals are positioning themselves to topple the Conservative government, now led by Ernie Eves. John Barber believes the prudent political mood that produced back-to-back election victories for the Conservatives - in 1995 and 1999 - has now shifted.

[John Barber] “The old ideas of big spending have gone, but so have the ideological ideas of about creating dependency and all that sort of thing. We’ve been through that, all that propaganda. I think people are really focusing on targeted ways of addressing some of our problems, which require public spending.”

David Miller agrees.

[David Miller] “That attitude is starting to come back. I don’t want to overestimate it, but people are starting to realize that this mythical promise of the right wing that we’ll cut taxes but you’ll still get all the same services is ridiculous. You don’t. What it means is visible decline in, in our case, the kind of city that you have.”

Toronto, a city in flux, forges on. Harris and Lastman may be, as John Barber says, “yesterday’s people.” But who are tomorrow’s leaders? And where will they lead the city? And just when is that election?

“November 10, 2003. And the polls close at 8:00 p.m.”

That’s David Miller. And I’m Stephen Miles.

Sources

Aubry, Jack. “Government can’t win on immigration:

Media sway public: poll.” National Post

(Late Edition), June 24, 2002, A4.

Barber, John. “Different Colours, Changing City.”

Globe and Mail, February 20, 1998, 1.

Barber, John. “Remarkable Experiment Playing Out.”

Globe and Mail, August 22, 1996.

Bourrie, Mark. “Population-Canada:

New Rules Could Shut Out Most Migrants.”

Inter Press Service, June 17, 2002.

Botchford, Jason. “T.O.’s Come Down in the World:

Lastman.” Toronto Sun (Final Edition),

May 29, 2001, 18.

Bramham, Daphne and Gordon Hamilton.

"Death of the Middle Class.“ Vancouver Sun,

November 17, 1992, A11.

Brennan, Richard. "Wrecking ball soon

back in city’s court.” Toronto Star (Ontario edition),

December 6, 2001, 3.

Bryden, Joan. “Coderre defends immigration plan:

Nothing to do with forced relocation, says minister.”

Edmonton Journal (Final Edition), June 25, 2002,

A5.

Burnet, Jean R. and Howard Palmer. Coming

Canadians: an introduction to a history

of Canada’s peoples. Toronto: McClelland

and Stewart, c1988.

Carey, Elaine. “The New Face of Poverty:

Toronto getting poorer while 905 thrives: Report;

'Poor are getting poorer, depth of poverty

is growing.’” Toronto Star (Ontario edition),

June 9, 2001, B1.

Cheadle, Bruce. “Population growth hits record low:

Immigrants the compelling story of 2001 census;

they’re driving growth and Canada needs more

of them.” St. John’s Telegram, March 13, 2002, A7.

Chidley, Joe. “The fight for Toronto.” Maclean’s

(Toronto edition), March 17, 1997, 46-50.

Coyne, Andrew. “Immigration critic out to lunch.”

Star Phoenix [Saskatoon] (Final Edition),

October 1, 2002, A8.

Crane, David. “Wilson, Crow, U.S. blamed for recession;

Free-trade pact had little effect, economists say.”

Toronto Star , December 7, 1993, D1.

Duffy, Andrew. “Immigration driving force for growth:

Big cities booming as immigrants flock to

hot job markets: 2001 census.” Ottawa Citizen

(Final Edition), March 13, 2002, A4.

Ferguson, Jonathan. “Canadians sing economic

blues as Mulroney exits.” Toronto Star,

February 25, 1993, B7.

Ferguson, Jonathan. “Tories blamed for job losses.”

Toronto Star, July 24, 1991, A1.

Gilbert, Leona. “T.O. Income Gap Grim;

City 'Spinning into Decline’: United Way.”

Toronto Sun (Final Edition), March 14, 2002, 24.

Gillespie, Kerry. “MPP joins rent hike fight.”

Toronto Star (Ontario edition), November 20,

2001, B4.

Gillespie, Kerry. “Official plan wins mixed reviews.”

Toronto Star, June 18, 2002, B3.

Gillespie, Kerry. “Toronto: The Next Generation.”

Toronto Star, September 14, 2002, B1.

Girard, Daniel. “Rent control revamp will

spur building boom: Leach; Housing minister

foresees 10,000 new rental units within two years.”

Toronto Star, June 13, 1997, A10.

Hiller, Susanne. “Suddenly, Toronto is heaven for renters:

'Landlords are cutting deals, offering incentives.’”

National Post, August 17, T1.

Hume, Christopher. “City can see clearly now that

Dundas has opened up.” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), July 1, 2002, B3.

“Immigrants are now our lifeblood.” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), March 13, 2002, A1.

Jacobs, Mindelle. “Jobs Can Lure Immigrants

to Smaller Cities.” Edmonton Sun (Final Edition), October 16, 2002, 11.

James, Royson. Battle threatens visionary plan

for Toronto.“ Toronto Star, September 14,

2002, A25.

Janigan, Mary. "Saving Our Cities.” Maclean’s, June 3,

2002, 22-27.

Krauss, Clifford. “Amid Prosperity, Toronto Shows

Signs of Fraying.” The New York Times

(Late Edition - Final), June 16, 2002, Section 1, p. 3.

Langan, Fred. “Job Losses to US Alarm Canadians.”

The Christian Science Monitor, December 11,

1989, 8.

Lazaruk, Susan and Kent Spencer and Christina

Montgomery. “Megacity Vancouver? It’s worth

a debate.” Vancouver Province, November 11,

2001, A2.

Levy, Sue-Ann. “Litter Bugged; Instead of studying

the problem, why don’t they just pick it up?”

Toronto Sun, October 10, 2002, 15.

Lindgren, April. “At age two, mega-city

still has mega-headaches: Torontonians have

discovered that making one giant city out of six

smaller centres is anything but easy.” Ottawa

Citizen, April 9, 2000.

Lindgren, April. “The mega-city everybody

loves to hate: All is not well in the amalgamated city

of Toronto, where mega-agendas and meetings are

causing mega-headaches.” Ottawa Citizen, April 27,

1998, A8.

Mandel, Michele. “T.O.’s Filthy Little Secrets Pile Up

Runaway Trashes Our Clean Image.” Toronto Sun,

November 7, 1999, 4.

Moloney, Paul. “Rent changes will hurt poor,

mayor says. Numbers of homeless will rise,

Hall fears.” Toronto Star, August 14, 1997, A8.

Ornstein, Michael. “Visible minorities in Toronto the

most likely to be poor, study finds.” Canadian Press

Newswire, July 6, 2000.

Perkel, Colin. “More than one million Canadian kids

still living in poverty, study finds.” Canadian Press

Newswire, November 25, 2002.

Michael Shapcott. “Affordable housing won’t

'trickle down’ to poor renters.” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), August 1, 2002, A21.

Siemiatycki, Meyer. “Immigration & Urban

Politics in Toronto.” Paper presented to the Third

International Metropolis Conference, Israel,

November 29-December 3, 1998.

Sokoloff, Heather. “Immigrants boosting growth of top

3 cities: Urban migration.” National Post

(Late Edition), September 27, 2002, A4.

Sokoloff, Heather. “Number of hungry children rises

33%: 'These children are still desperately poor,’

Louise Hanvey, author of child poverty report says.”

National Post (Toronto edition), November 5,

2002, A6.

“Sounds Just Like A Plan.” Toronto Sun (Final Edition),

October 18, 2002, 14.

“There was no boom for the poor.” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), May 2, 2002, A28.

“The shape of poverty in Toronto.” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), June 9, 2001, A01.

“Toronto must confront suburban poverty,” Toronto Star

(Ontario edition), March 25, 2002, A18.

“Tory Rent Reforms Worsen Shortage.” Toronto Star,

October 11, 1999.

Usborne, David. “Canada Invites Mirgrants to Help

Reverse Rural Decline.” The Independent [London],

October 3, 2002, 16.

Walker, Michael. “As rents climb, nobody protects

tenants.” Toronto Star (Ontario edition),

August 13, 2001, A13.

Walker, William. “Blue tide of change Harris-led

Conservatives roll to majority government.”

Toronto Star, June 9, 1995, A1.

Willis, Victor. “A day to demand housing for all.”

Toronto Star (Ontario edition), November 19, A32.

“Yonge/Dundas Regenation out of the starting gate.”

Canada NewsWire, May 6, 1997.

Credits

“Toronto: City in Transition” was researched, written, recorded, edited and narrated by Stephen Miles.

He would like to thank Professor Jack Mitchell, Yael Gen, Larry Davidson, Joel Lorberblatt, Frank Miles, Grace Miles, Veronica Ruekert, A.J. Dubois, Kathy E. Esch, Thrill Jockey recording artists Mouse on Mars and Town and Country, Temporary Residence recording artist Fridge, Mary Janigan, James Lemon, Jean Burnet, Craig Kois, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Access Toronto, the Toronto Public Library, WLUW, WORT, and everyone whose voice is heard in the documentary.

Special thanks to audio adviser Joshua Dodge.

By late 2000, the vacancy rate in Toronto had dropped to an 11-year-low of .6 percent, barely improving since then.

City Councillor Kyle Rae believes that government policy – or the lack of it – has produced Toronto’s housing crisis.

[Kyle Rae] “In 1993, the federal government terminated its affordable housing program across the country, which has meant that we no longer have any support from the federal government in terms of building affordable rental accommodation. In 1995, the provincial government changed, and that government terminated its affordable housing program.

"It’s an appalling dilemma that we find ourselves in, and we’ve got two levels of government that are – I would call them deadbeat dads. They are senior levels of government; they are responsible for housing; it’s in their portfolios, and they have walked away from them. And it is a national shame.”

One of the first actions of the Harris government was to terminate Ontario’s nonprofit housing program. Next, the province stopped subsidizing low-income tenants in existing apartments by pulling out of the so-called rent supplement program.

Then came the Tenant Protection Act. Before Housing Minister Al Leach had even introduced the bill, Toronto Starcolumnist David Lewis Stein was considering renaming it. Stein suggested “the landlord benefit act.” Or perhaps, “the overextended developer rescue act.”

The point was obvious: the Conservatives did not actually have tenants in mind when drafting legislation in their name.

And the bill itself did nothing to allay those suspicions. The government proposed to overhaul the city’s 22-year-old rent control system to provide a stimulus for new development.

With rent controls lifted on vacant apartments, Housing Minister Al Leach predicted that construction would begin on 10,000 new rental units within two years.

Leach’s 10,000 new units did not materialize – barely 200 units were added to the city’s stock during the first 12 months of the legislation’s enactment.

Critics were finding no shortage of data corroborating their bleakest predictions. One critic reported that rent hikes of 30 to 50 percent were not uncommon. Another charged that the “Orwellian-named” Tenant Protection Act had “turned tenants into cash cows for its friends, the landlords.”

Urban scholar and former Toronto resident Jenny Burman believes that strict rent controls should “absolutely” be re-instated.

[Jenny Burman] “What I’m afraid of is that it is becoming a more expensive place to live, and a harder place to live downtown. And eventually, if it goes at this rate, people who do live downtown now will be priced out.”

Many newcomers to downtown Toronto are also finding rents difficult to manage. Thirty-eight-year-old Nazir Ahmed lived with his family in a large three-bedroom apartment in his native Bangladesh.

[Nazir Ahmed] “Here, I live in a junior single-bedroom apartment with $1,000 dollars rent. Housing is very expensive. I think it should be controlled.”

Meanwhile, condo development continues apace.

Extra text segment: Mega-city

John Barber: “As a columnist … I was very very much against the mega-city. I thought it was a terrible political initiative that would be an expensive boondoggle, and would not accomplish its goals of saving money or making government more accountable. I hate to say that I’ve been proven right beyond my wildest dreams. Everybody knows it’s been a disaster.

It’s that political disaster which basically removed, has turned municipal government into a negative force. They just haven’t been able to move forward in any way. It’s really unfortunate. Just the difficulty of reorganizing the city has absorbed the city government’s energies. And there have been corruption scandals, too, that are unprecedented in the history of this city, at least in my time. So it’s been a very very negative experience for this city, and it’s certainly an important part of the reason why Toronto as a city is floundering to a degree it hasn’t.

But most of us recognize that it’s not going to go back to what it was; that this structure is like any other structure: it can be made to work. And I’m looking forward to a day when the bugs are worked out, and we can actually make this ungainly thing operate the way its supposed to.

Councillor David Miller: Amalgamation was probably not the best idea in the first place, but was very rushed and politically motivated. They didn’t like the government. It was sort of like Margaret Thatcher getting rid of Greater London Council. The government in Toronto was perceived to be left wing; they [the Conservative Ontario government] were hard right radical Republican Tories, which isn’t a Canadian tradition (our Conservatives are different than Republicans traditionally). They decided they wanted to get rid of it. No thought, no planning. And then they proceeded to cut all sorts of funding the city had and give us responsibilities we didn’t have in the past; all of which made amalgamation even harder, because there was no money to go around.

Andrew Pyper: I think it was an instrument that was sold to the people of Ontario – of Toronto – as cost saving; this will be more efficient. And it’s indifferent. "This isn’t a political move, this is just good sense.” And “streamline.” Words like that.

On another level, though, it was an instrument that allowed for the government of Ontario to neglect, without apology, problems that were distinct to downtown Toronto. If you amalgamate, if you just call this sort of big rectangle that goes from the lake to King City … just call that Toronto, then the particular problems that are unique to downtown Toronto can be easily overlooked, whereas [they] couldn’t before. So what looked to be a-political, or just strictly an efficiency-based decision, was, of course, politically-based. And it succeeded. It was a brilliant tactical turn by the Conservatives, because it has allowed them to treat Toronto like this block of similarly-situated communities. And, of course, it’s not.

Extra text segment: 30-year plan

Councillor David Miller: [Toronto’s official 30-year plan] is an environmentally-friendly vision, it’s a people-friendly vision, it’s a transit-friendly vision. But some groups of citizens are nervous, because it means their neighborhoods will get bulldozed and just replaced with apartment buildings, which is what happened in Toronto in the late '60s and early '70s because there was just wild development.

What you need to do is control that development and direct it so that it works for the city as a whole. The intent of our new official plan is to try to do that. But there is some concern – legitimate concern – among some citizens about whether it will or not. That’s an important issue, because if we don’t start building in the city, we’re going to be in trouble.

Councillor Kyle Rae: The official plan has been worked on for three years and I’m very pleased to be an advocate for it. It’s quite clear, if you look at it, that it makes very little change to the inner-city or the downtown. What it’s trying to do is weave the new parts of the city into the old, and it’s using planning studies of avenues where intensification of residential and transit should occur as the spine along which our new city should be focusing its intensification. For the most part, there is very little change in the inner city where I represent, and it’s very easy to support.

But members of council have been fear-mongering that this official plan will destroy their neighborhood. The reason why they’re saying that is that this official plan will be removing any height or density numbers from the plan for the first time. And although we’ve wanted to do this for many years, it has not been achieved until this year. So members of council who oppose the plan have been arguing that the protections, in terms of zoning and height restrictions, will be lost; when, in fact, they exist in the zoning bylaw and they will continue to exist until the zoning bylaw [is] amended by staff and consultation with neighborhoods and then approved by council.

So the first step is to clean up the official plan and make it that visionary document that an official plan is meant to be. Then deal with the specifics of height and density in the zoning bylaw, which we hope to see in the next five years.

Councillor Howard Moscoe: I think the underlying basis of the official plan is a good idea. I think basing the plan on public transit is a necessity. I think planning for growth is essential. The reservation I have is that it withdraws from me some of the tools that I need to negotiate with developers, and most development in Toronto is negotiated on a case-by-case basis between the community and the developers.

The tools at my disposal are spelled out in Section 37 of the Planning Act, which essentially says, if a developer wants to exceed the density and the height limits of the plan, he can buy that through negotiations with the community, through community benefits. So if a developer wants to build 20 percent in excess of what the official plan allows, I have a right to sit down and negotiate community benefits like a new park or a daycare center, or any number of those kinds of things.

My fear is that because the official plan is too loose, I lose the right to do that. They’re taking away some of the tools that I have to engage in those negotiations, because they’ve eliminated from the plan the maximum densities. They’re saying density doesn’t matter anymore, that height is less important than built-form. And that sounds very good in theory, but I’m still grasping with what tools I have at my disposal to do these negotiations.

Extra text segment: Yonge Street

Thirty years ago, retailers on lower Yonge Street claimed a quarter of the metropolitan area’s shopping dollar. By 1994 that figure had dropped to 5 percent, the proliferation of suburban shopping malls and competing downtown retail districts accounting for part of the downturn.

Meanwhile, Yonge Street’s decline was being dramatized by a series of unsettling incidents. One involved the rape and murder by three men of Emanuel Jaques, a 12-year-old shoeshine boy whose body was found on the roof of a Yonge St. body-rub parlor in August 1977.

Fifteen years later, the acquittal of four white Los Angeles police officers involved in the videotaped beating of Rodney King triggered two nights of looting and mayhem along a 20-block stretch of Yonge Street.

But the Yonge Street business community knew of another factor accounting for Yonge Street’s visible decline: the Eaton Centre.

Ron Soskolne: “Eaton Centre was built in the 1970s and was very glamorous, but in planning terms a typically suburban shopping mall. The downside of the Eaton Centre is that it sucked almost the totality of the high- and middle-income retail life of the street into the mall and left a vacuum out on the street.”